We all write short stories and novels. For me, the process is very different. I often use short stories to try out ideas, where a novel is something that I plan meticulously. How do you organise the two narrative worlds? What did you write first, novels or short stories?

TESSA: I felt that I could write short stories before I quite knew how to manage the great beast that is a novel. At first I tried just putting short stories end to end. That worked. Now I’m beginning to feel more confident with the longer lines of the novel.

CARYS: For me, the process is different, too. I’m not sure whether I’d describe myself as a meticulous planner when it comes to novels; I’m more of a beginning and end planner – the middle tends to be beaten into shape as I go. I plan short stories in a similar way but their weight and shape renders them more pliable. I suppose it’s like the difference between attempting to knead a one-pound and a ten-pound loaf of bread.

I wrote short stories first. I love the elasticity of the short form – stories in the same collection can be surprising, contemplative, horrifying, magical, speculative, experimental, and so on. I love the way short stories can capture a moment or, in Alice Munro’s case particularly, hold the essence of a whole life. Short stories can explore those ‘what if’ ideas you might have: what if you bought your children at the supermarket, what if the witch in Hansel and Gretel is a harmless old woman? Neither of those ideas has anything like the momentum or depth for a novel (not in my hands, at least) but they’re potentially interesting.

Initially, didn’t have any plans to write a novel and there were also matters of permission and time: I didn’t think of myself as a writer back then and as a result I didn’t feel I could invest huge amounts of time in writing. I used to write during the day when my children were at school/nursery. In the evenings, I’d keep my laptop open while I cooked or helped with homework and I’d edit things or make notes as I had new ideas.

We had a short story event here last year with Claire Dean, Michelle Green, David Constantine and Stuart Evers, and we discussed the origins of short stories. Both Claire and Michelle felt very strongly that short stories have evolved from folk tales and still bore the traces of their origins. Whereas Stuart Evers, and to an extent, David Constantine, felt that the modern short story is about 100 years old and quite different from folk tales. Which side of the fence, if any, do you both fall on?

CARYS: Give me a fence and I will sit on it! I think of Katherine Mansfield’s ‘Bliss’ and can’t immediately see a connection with folk tales (the image of the pear tree is nudging me, but I may be reading too much into it now that I’m searching for a connection/some roots). Having said that, I can see folk tale roots in other stories of that time. Can I have my cake and eat it, please?

‘Sweet Home’ (the story, as opposed to the collection) is clearly an adaptation of a fairy tale. I wrote ‘Sweet Home’ because I always felt that the old woman in Hansel and Gretel had a bad deal. She had made a beautiful house and then two children came along and started eating it. It reminded me of the effort I used to put in my children’s birthday cakes and how it subsequently felt to see them demolished.

TESSA: I think that the short story as mostly practised in the UK tradition is probably more like an off-shoot of the novel form. However, just because its length is something like the length of an extended anecdote, or a joke, or a story for children, it can take on something of those intonations. In the US it’s often – in the hands of Twain or Hawthorne – more like a tall tale or a parable. Perhaps there the literary culture kept closer, at least for a while, to oral culture.

To what extent do you write from experience and to what extent imagination?

TESSA: I’m not sure I can separate out experience and imagination. I’m not sure you can have much experience that’s worth writing about without imagination.

CARYS: I use a mixture of experience and imagination. I’m not aiming for reflection – for refraction, perhaps. For example, my second novel The Museum of You is about single fatherhood, something that’s outside of my experience, but I know how it feels to be a parent and I understand loss and loneliness and am interested in exploring those themes in my writing.

I think a lot of my stories are about characters that are trapped in some way. And I see it to an extent in both of your collections. Tessa, a lot of your protagonists are women trapped by middle class mores, yearning for some kind of escape. Which never comes through. Do you agree?

TESSA: My stories aren’t about women who are trapped. I don’t think ‘trapped’ is a very useful way of thinking about how any of these characters are caught up in the envelope of their particular circumstances. I think I prefer the idea that ‘stuff happens’ to people, and the stuff is sometimes fascinating.

Carys, some of your protagonists are women trapped by the mores of middle-class motherhood. You write, to an extent, about the domestic space, in relation to mothers and their children. To what degree do you think it is still gendered?

I think 8 of the 17 stories are explicitly about motherhood (perhaps even middle class motherhood, although I’m not entirely sure about that – the woman in ‘Just in Case’ is a shop assistant). ‘The Rescue’ concentrates mainly on fatherhood, as do ‘The Ice Baby’ and ‘The Countdown’ and the remaining stories are about older people (mostly women) or children.

I don’t see the domestic space as inherently gendered, despite that fact that it is, at least in Sweet Home, a space primarily peopled by women. We all eat and sleep somewhere. We all put on clothes in the morning and partake in a variety of domestic routines. I do think that women writers are asked to comment on ‘the domestic’ more than male writers. In fact, I keep a few quotes to hand for such moments. Let me find them…

Here’s what Helen Simpson had to say about it: ‘That domesticity word is politically loaded. It’s used to describe something as tame or boring. It’s anything but.’ From Kate Mosse, ‘…when men write about domesticity, it’s seen as great literature. When women do it, it’s seen as women’s issues.’ And Carol Shields: ‘now that men are writing so-called domestic novels they are not called [domestic] at all; they are called sensitive … reflections of modern life’; ‘[w]hen men write about ‘ordinary people’ they are thought to be subtle and sensitive, when women do so their novels are classed as domestic.’

I’m aware that I’ve used a lot of words and not really answered the question, so I’ll pull myself back to it. To what extent is the domestic space still gendered? In a general sense, I don’t know – that’s the kind of question I’d like to approach with a reading list and at least 10,000 words. To answer more specifically and personally, I wrote the stories in Sweet Home 8 years ago, after a decade of being at home with 4 children. The domestic space certainly felt gendered to me at the time. In the years since, that has changed and, for me, at least, the domestic space in my life feels less gendered, less lonely and more collaborative, and I suspect that is reflected in my writing.

Carys, your collection is very themed. The problems of parenthood to a large degree. Did you conceive of the collection as a single thread? Or is that just how it worked out?

CARYS: I wrote the stories during my MA, so they were written over a period of about 12 months and they reflect my preoccupations at the time. My children were small(ish) and I was thinking about parental ambivalence and the way families work (and don’t work).

Initially, I wasn’t imagining the stories as a collection. My writing was inspired by all sorts of things: snippets of conversation, real life events, one of my favourite poems – The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock, fairy tales, and even a poster I used to walk past at Edge Hill which posed the question ‘How High Should Boys Sing?’ I was also inspired by some of the strange and magical stories in Adam Marek’s Instruction Manual for Swallowing and Robert Shearman’s Love Songs for the Shy and Cynical. It was only after I had a good chunk of material on which to reflect that I could see the common theme(s).

How important is order in your collections?

CARYS: I thought carefully about the order of the collection. I had post-it notes stuck to my kitchen cupboards in various orders over a period of time as I tried to work out how best to place the stories. In the end, I tried to arrange the stories so that there was some variety in length and theme; to intersperse the sad with the humorous and so on.

After Sweet Home was published, a poet friend asked if I had thought about how the closing image of each story interacted with the opening image of the next, which relates to your question, above. I hadn’t, and I suddenly wished I had. I went home and looked at the opening and closing images of the collection. It was then that I realised Sweet Home opens and closes with the same image, a mother on her knees – I’d like to pretend I did that on purpose, but it was an accident.

TESSA: I try to find a good rhythm between the stories.

What are your favourite short stories and writers?

CARYS: My favourite short story is probably Kate Clanchy’s ‘The Not Dead and the Saved’. It’s a remarkable story – as it concludes, a tiny piece of information that has been withheld is revealed and the whole story opens in the most satisfying way.

I have been hugely inspired by Carol Shields. I discovered her novels and short stories in the final year of my BA. Shields had five children and her first novel was published in 1976 when she had just turned forty. It was her writing that really made me see that there is beauty and interest in ordinary lives.

I love the short stories of Adam Marek and Robert Shearman – I admire the way they find magic and absurdity in the everyday. The same goes for Ali Smith’s short stories. Helen Simpson’s stories were recommended to me while I was studying at Edge Hill and her writing was very influential – it’s beautiful, observant and funny.

TESSA: Kipling, Chekhov, Alice Munro, John Updike, Mavis Gallant, Lucia Berlin, John McGahern, Agnes Owens, Colin Barrett & many more (but not that many).

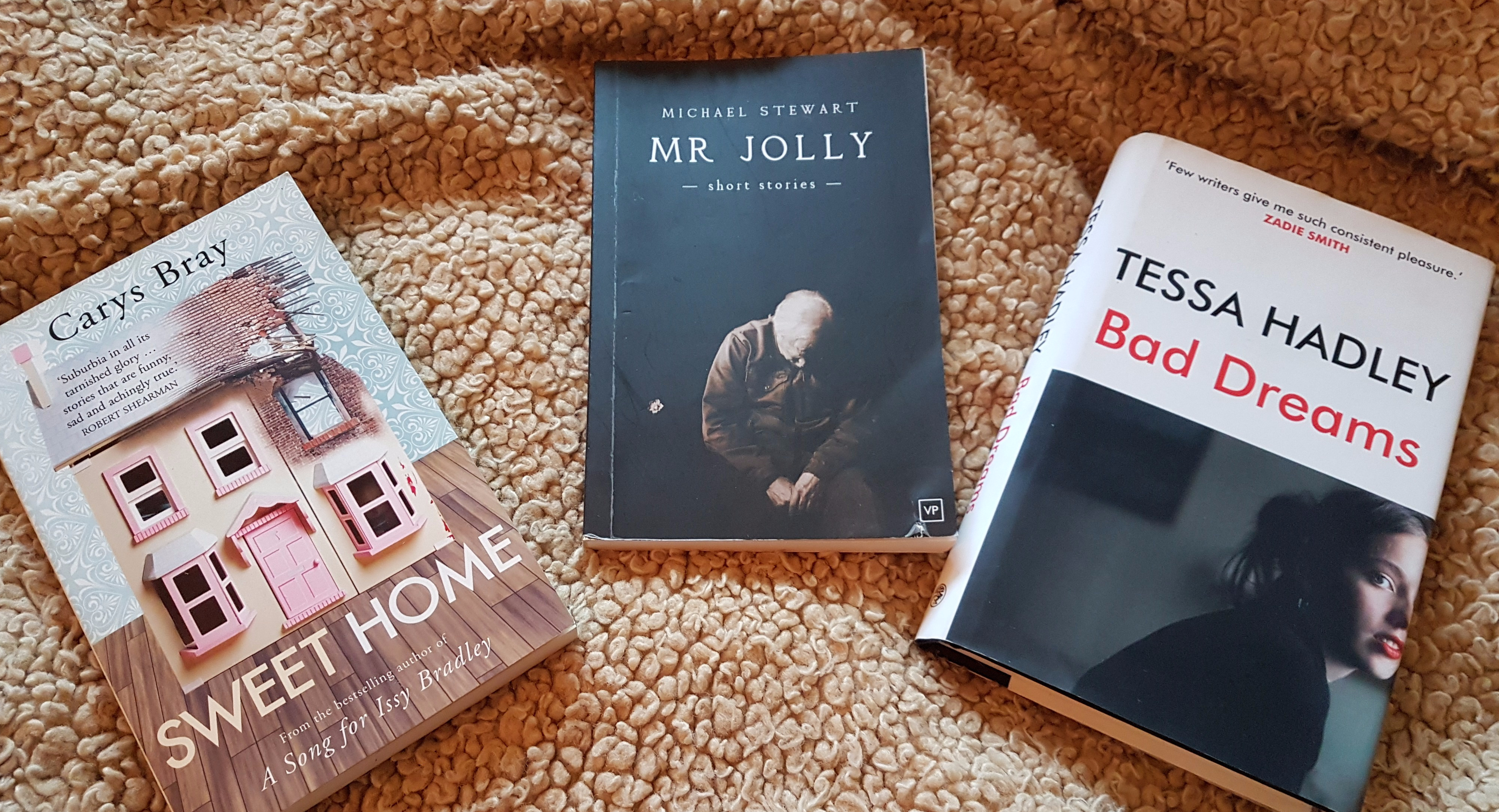

Thank you both very much for taking the time out to answer my questions. Sweet Home by Carys Bray and Bad Dreams by Tessa Hadley are both available from the usual places. And I highly recommend both books.