I’ve just read Where the Road Runs Out, Gaia Holmes’ third poetry collection, published a few months ago by Comma Press. I’ve enjoyed all her work to date, but this feels like her strongest most accomplished collection, and I want to find out more about the background to the poems that novelist Sara Maitland calls ‘incantations’ and ‘witchcraft’.

I pick Gaia up in my van. It’s a crisp and misty autumn morning. She lives in a flat in Halifax, part of a large Georgian House. She shows me where the door and handle to her flat have been damaged. There was an attempted break in the other week. But the offender was not trying to steal anything. He was looking for an empty flat so he could squat. The Georgian house is one of former splendour. The hallway is grand with a sweeping staircase and beautiful oak bannisters, but the paint is peeling off the walls and the plaster bubbles with damp and water damage.

We drive through low mist which clings to spindly trees, towards Warley village, on the outskirts of Halifax, where Gaia spent her formative childhood years. We park up at the Maypole pub and cross over to examine the church over the road. It’s an imposing block of stone, with two turreted towers with crenelated crowns. Next to the chapel is a house called The Grange. Patrick Brontë lived here for a short while. Gaia grew up in the chapel which was bought by her parents and renovated. We stand beneath, in its shadow.

‘It’s an incredible bit of architecture but not necessarily an obvious family home.’ I say. ‘When did you move here?’

‘I was about six.’

‘Who was pushing the move? Your mum or your dad?’

‘Definitely my dad.’

‘And did he have building skills? Did he have construction site experience?’

‘Yeah, I mean he didn’t adhere to any health and safety rules though. There was a lot of gaffer tape involved.’

‘Where did he acquire those skills?’

‘I don’t know. He must have taught himself. He had these DIY magazines.’

We walk round the outside of the building. It hasn’t been a church since 1977. She tells me that before this they were living in a cottage in Luddenden.

‘So what prompted the move?’

‘It was just my dad. He had big dreams.’

‘How was he earning a living at this point?’

‘He did loads of stuff. He was a taxi driver, he was a handyman, he had a burger van. He kept getting it pushed over. There were lots of burger wars.’

‘But he became a vegan later though?’

‘Yeah, he did.’

‘So you were six years old. Can you remember being excited about the prospect of moving to a church?’

‘I just remember, in the backyard, we had a caravan, and me and my brothers, Jago and Rudolf, and my mum and my dad, and five cats, all living in this caravan and it was freezing. When you look at photographs, all the windows are steamed up, but I think we quite liked it really.’

‘So you lived there until it was renovated?’

‘Yeah. We moved into the front bit first. It was very primitive. You’d walk through all this building rubble and cement bags, into this furnished room with deep pile carpets and velvet curtains. It was very strange. We had pews and a pulpit.’

‘But your father wasn’t religious?’

‘No.’

‘Does it seem a bit perverse, as a non-believer, to want to live in a church?’

‘Possibly. He was a very contradictory character.’

‘What else do you remember?’

‘That clock tower.’

She points to the large opaque face towards the top of the building, with big black Roman numerals.

‘There was a room behind the clock and I used to hide in there. And I could see the street below, watch the people come and go. But they couldn’t see me.’

‘What were you hiding from?’

‘I was skiving off school.’

‘Why?’

‘I didn’t like school. I got bullied.’

‘What were they bullying you for?’

She shrugs, ‘Because I was a hippy. And I lived in a church. And because my dad was my dad.’

She tells me that she lived here until she was seventeen when she moved out on her own to a high-rise tower block in Mixenden. On the top floor. Mixenden is an odd place, where urban tenements rise out of the middle of a rural landscape. When film makers want to suggest bleak and quirky, it’s the go-to location. It’s quite beautiful too in places. You can walk down from those flats to the beck that runs through the settlement. The trees are hundreds of years old and there is an ancient clam bridge over the beck.

‘Seventeen is quite young isn’t it? Were you at college or working?’

‘I couldn’t really cope with the bullying at school so my parents took me out of school and home educated me. My dad’s idea of home education was to give me GCSE pass books. I would work through them in his gallery. Then I went to the Steiner School in York and I didn’t like it there either.’

‘But they’d all be hippies there?’

‘Well, no, but at that point I was trying to fit in and I’d permed my hair and I was trying to conform. I was wearing teddy bear jumpers.’

‘You were caught between two worlds. So, you moved into your flat in Mixenden. On your own?’

‘Yeah, just me and a pet rat, Clovis.’

‘And did your family live in the church after that?’

‘For a bit, yes. My mum had moved out. Then Rudi moved out. Jago worked on the building with my dad. Then he bought the back and turned it into a gym. My dad moved to Shapinsay.’

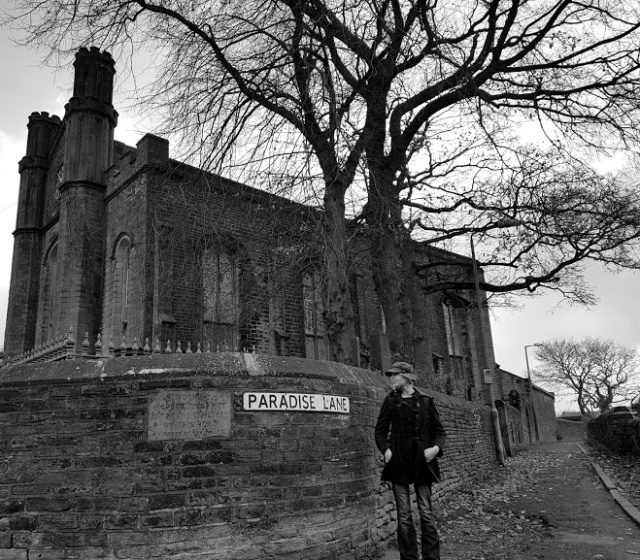

We walk down Paradise Lane to the other end of the church.

‘This is where he had his kiln here.’

She points to a room which is partially beneath street level. Her father made ceramics to sell in his gallery which was situated in the repurposed Piece Hall in Halifax. He made Raku teapots. I contemplate the sombre, gothic exterior. I imagine a dark and cold inner world.

‘What was it like to actually live here? Did you have bad dreams?’

‘No, I loved it. All that space. We had a rope swing off one of the beams, and I used to swing from the balcony. There was a mattress underneath. It was an idyllic childhood, and quite free.’

‘But at seventeen you decided to move out?’

‘I think I just decided “I’m an adult now”. Even though I wasn’t an adult. I got a job. Like a YTS scheme. I worked at a day care centre in Ovenden for about two years.’

We walk away from the church further down Paradise Lane, towards the town primary school. The school that Gaia attended as an infant. We stop at some railings and peer into the play area.

‘Were you happy here?’

‘It was a good school. I loved it.’

‘That’s funny. I loved primary school too but I absolutely hated secondary school.’

‘Did you get bullied?’

‘No, but what happened, really in the first week, we were given an exercise to determine what groups we were to be put in. We had to write about a room. Any room. I went home and thought about it. I wrote this story about a character who wakes up in a room and doesn’t know where they are or who they are. It’s a round room, very small, with no windows or door. And they are confused. The walls are opaque and crimson light pours through. There are muffled noises. It ends with this blinding white light, which the character is pulled towards. We find out it’s a foetus being born. I was really pleased with it, but the teacher gave me an F for fail.’

‘Really? How come?’

‘She said, “I asked you to write a story about a room and you write this stupid story about being born.” I was put in the bottom class.’

‘That’s mad.’

‘After that, I just decided to subvert everything I was asked to do. It was a stupid game that I could only lose. By the end of the year I had been excluded from school for twelve months.’

We are walking across the village’s recreational fields. We turn left at the end and head down the lane past The Vandals rugby club. We cross a field with two stampeding horses until we reach a clearing, and the valley of Luddenden. The mist has cleared but still hangs low in the distance. Silver sunbeams cut through the mist illuminating the valley below. The beams look solid, like the steps that lead to heaven in Branwell Brontë’s painting ‘Jacob’s Dream’. He worked at the station at the foot of the valley until he was dismissed for misappropriating some money. There’s a statue of him where the station used to be. It is one of the worst examples of public art I have ever seen. The figure doesn’t even look human. It looks like a deformed, obese leprechaun.

‘Mist features heavily in your collection, doesn’t it? The first third of the book is really about the time you spent on the island of Shapinsay, off the Orkney Mainland, looking after your dying father. And mist is an integral feature. A lot of the poems describe mist. You call yourself The Mistress of Haar, which is a kind of sea fret.’

‘Yeah. It’s very cold. Often unexpected. It can be sunny, then in five minutes the island can be completely shrouded in this cold mist.’

‘Place and situation, in that section of the book, have a perfect marriage. The island is one of the Orkney islands off the north coast of the mainland. It is geographically on the edge. And the island itself is exposed to the elements of the North Sea. Your father in your book, is reaching the end of things too. The book is called Where the Road Runs Out, and that applies to both the geography of place, but also to a man’s life. It almost becomes the same thing. That sense of the end of things, the edges of things. The mist, the barrenness, the harsh weather. Were you aware of that as you were writing about place and person?’

‘The island, in my head, came to represent my dad. Before my dad got ill I used to really hate the island because it’s very exposed. It takes two days to get there. You travel to Aberdeen. You get a ferry to Kirkwall, which is on the Orkney mainland. The ferry doesn’t get in till 11pm, and the boat out to Shapinsay doesn’t go until 8 in the morning. So you have to stay over. But spending all that time with my dad there, I came to really love the island.’

‘But it’s a hard place to live.’

‘He had to keep his caravan from flying away by anchoring it with three tonne of cement blocks. Sometimes he would have to crawl on his hands and knees from his caravan to the mill where he had his pottery works. Or else the wind would have blown him away.’

‘That’s the caravan on the front cover of the book. It’s a lovely cover. But very bleak, just a gull and a caravan.’

‘And a load of pylons.’

‘I was going to ask you about that, why so many pylons?’

‘That’s just a reference to one of the poems.’

‘Yes, of course, “What Pylons Dream Of”.’

It’s a good example of surrealism. In the poem, the pylons dream of stepping into ball gowns.

‘That first third of the book is almost a chronology of your time nursing your father as cancer ravishes his body. That section ends with the poem “Kummerspeck”, which is a German word. It literally translates as “grief bacon”. It is a very visceral response to grief. It makes grief an actual physical thing that feeds on blood and flesh. There’s a line about the fridge stinking like a butcher’s gutter. But then the rest of the book is business as usual. Only you come back to him further on in the book as a ghostly figure. And there are lots of holes in the book.’

‘There’s a poem about a sinkhole.’

‘But not just sinkholes, other kinds of holes too. Is one of the holes that left by your father’s passing?’

‘I wasn’t going to include those poems. I was going to move on with my life. I had a collection that was a mix of subjects. There’s a poem about pylons and a poem about runners, a poem about childlessness.’

‘I love that poem. It’s called “Ballast”. I remember you reading it years ago, at an event, and it put a chill right down my spine. I’m so glad you included that poem. I’ve heard you read it several times since, and it has always had a profound effect on me.’

‘I was a bit wary about putting it in the collection because it was based on an experience that really happened. I went to my friend’s house and there were some other friends there I hadn’t seen for a while. I didn’t have to do much with that poem. I just put down what happened.’

‘It’s a remarkable poem. There is so much emotion in it, but it isn’t a bleeding heart poem. It’s about a woman, you, who has reached a stage in her life, where she spends a lot of time holding other people’s babies. It’s a party where M & S berry crushes outnumber wine bottles and you are the only one drinking. All the women there are mothers and they are talking about teething rings and Farley’s Rusks. Then you go outside for a cigarette and when you, or the character in the poem, returns, she senses that the women have been talking about her with pity. And there is a sense that you, or the childless woman in the poem, have become an image from a horror film. It really hammers home how much women are still defined by these roles. In fact, self-defined. Like the child is almost a fetish object and we all have to worship it. It’s a type of tyranny. Is that how you feel?’

‘Parts of me. The strongest thing for me is that you are not seen as a woman if you don’t have a child. That you are a freak.’

‘That’s so odd now, isn’t it? In this day and age. We live in an overpopulated world of dwindling resources; we should be encouraging childlessness in all its forms. And yet we have this post-feminist world that, in a way, has stepped backwards.’

She nods as she stares out over the valley, at the sun shining through the mist, and the leafless trees.

‘And the womb is another hole?’

‘Well, yeah, that was the idea.’

We reach a footpath that leads into Hollins Wood. We enter the woods and approach a clearing. The forest floor is thick and spongy with fallen leaves, and some leaves still cling to the branches above: copper, yellow and gold chevrons. Like the few feathers clinging to a plucked chicken.

‘This is the wood I used to come to when I moved back from Mixenden.’

‘Under this tree?’

‘We christened these two trees. One was the Grandmother Tree and the other the Grandfather Tree, but I can’t remember which. I felt really safe here. I slept out here a few times.’

‘By yourself or with friends?’

‘Both. I’ve slept here by myself a few times.’

There are still remnants of the fire pit Gaia built to keep herself warm. A rough circle of stones with a charcoal lined inner.

‘And you wrote poems here? By this fire pit?’

‘Yes. I was sending them off to magazines. I just couldn’t stop writing. I had this urge to write and it was lovely. I still have that urge but it’s nothing like as strong.’

‘I know what you mean. It’s almost like a drug. It overtakes you. It intoxicates you. You’re almost giddy with it. Your mum lived in these woods didn’t she?’

‘Yeah, but only for a few weeks. By that waterfall. She made a bender, and lived in it.’

We sit on a fallen tree trunk and drink hot black sweet coffee out of a flask. I take out my copy of Where the Road Runs Out.

‘I want to talk a bit more about the imagery in the poems, if that’s ok? For instance, this poem here,’ I turn to the first poem in the collection, ‘And Still We Keep On Singing’ and point to the last stanza. ‘“Candles whose wicks are too damp and weak to sustain a flame.” That’s your dad isn’t it?’

‘I like it when people do that. I hadn’t thought about that.’

‘I was intrigued by the poem “Leaves”. In the poem, when your dad is dying, you post him bags of leaves.’

‘You don’t see autumn on Shapinsay, because there are hardly any trees. It was late September and there were all these beautiful leaves, and I gathered them and put them in a parcel and posted them to him.’

‘I like it where you use metonyms. Is that the right word? There is a line of washing, his socks next to your dress. There is an image of red wine next to Complan. You are the red wine. Your father is the Complan.’

‘It’s known as objective correlative.’

I flick through the pages. ‘This line here, “the wrong kind of holy water”. Does that refer to alcohol?’

‘No, when he was dying he kept ordering these miracle cures from America.’

‘What sort of things?’

Caesium chloride was one. It’s basically a bleach. It was awful. My dad never struck me as gullible, but it cost three hundred quid to post this stuff from America. And he thought it would save him. He tried Cannabis Oil and Bloodroot. It burns your skin.’

‘And this line “the rain pelts like pearls” it’s an interesting oxymoron.’

‘When you’re in a caravan, you hear the rain on the roof like a drum. And the winds. I mean, a 50mph wind is nothing. On a night, when it’s all windy and wild, you feel cosy inside.’

‘And it’s rocking, almost like a boat?’

‘Yes, very much so.’

I put my book away. We finish the coffee. We walk out of the wood towards Luddenden village, making our way down a steep cobbled road, with worn undulations from cobbled soles, to the Lord Nelson pub, the same pub Branwell Brontë drank in, when he was Station Master at Luddenden Foot Station. I order a white wine for Gaia, and a pint of White Witch for me. We sit down at an old oak table, scratched and scarred with time. We’ve left the poems behind but one particular image haunts me.

‘I just want to come back to this line. You have the mist of the landscape, and the fact that your father’s breath isn’t strong enough to mist the mirror that you hold up to his mouth.’

‘It was a strange time. I was on my own with him. He spent his last days in hospital on the mainland, in Kirkwall. I’d have to commute from the island. I’d come home in dark. I’d walk up this hill in the wind and rain, and the street lights would run out and I’d be in complete darkness. I used to leave the lights in the mill on so that I could see where I was going. And as I got close, his three cats would be sitting outside, waiting for me.’

Where the Road Runs Out by Gaia Holmes is published by Comma Press. You can buy it here.

Ill Will: The Untold Story of Heathcliff by Michael Stewart is now published in paperback by HarperCollins. You can buy it here.

I first conceived of the Brontë Stones project in October 2013 while taking a group of writers along another literary trail. I live in Thornton and have long wanted my village to receive recognition for its place in the Brontë story. All three literary sisters and their wayward brother were born here. I thought about the journey they took in 1820, over to Haworth. They were a happy family, but very shortly, after their move to Haworth, tragedy struck. First the death of Maria, the mother, then the two oldest siblings.

I first conceived of the Brontë Stones project in October 2013 while taking a group of writers along another literary trail. I live in Thornton and have long wanted my village to receive recognition for its place in the Brontë story. All three literary sisters and their wayward brother were born here. I thought about the journey they took in 1820, over to Haworth. They were a happy family, but very shortly, after their move to Haworth, tragedy struck. First the death of Maria, the mother, then the two oldest siblings.

Nigel Blackwell of Half Man Half Biscuit fame is an elusive figure in popular music, who has spent many years avoiding interviewers from many prestigious publications, so I feel very honoured that he was happy to answer the questions I had after listening to the latest album Urge For Offal. It’s as good as anything the band have done and if you haven’t listened to them for a while, it’s a great introduction to where they are now.

Nigel Blackwell of Half Man Half Biscuit fame is an elusive figure in popular music, who has spent many years avoiding interviewers from many prestigious publications, so I feel very honoured that he was happy to answer the questions I had after listening to the latest album Urge For Offal. It’s as good as anything the band have done and if you haven’t listened to them for a while, it’s a great introduction to where they are now.